Public opinions about government response to COVID-19 might shift if people had witnessed the protests that emerged in response to those actions. However, one could argue that such protests might not have been necessary at all if more young people had actively participated in the electoral process. Many youths, disillusioned with politics and quick to dismiss it with phrases like “I hate politics,” have inadvertently allowed ineffective leadership to rise. When citizens disengage, democracy weakens.

While youth involvement in protest is crucial for driving systemic change, these demonstrations often focus on isolated issues rather than the broader, underlying structures. In conversations surrounding the COVID-19 protests, some suggested that youth participation was less about the cause itself and more inspired by global movements—particularly the U.S. protests following the death of George Floyd. For some, protesting became a symbol of modernity or global cultural alignment—akin to wearing Western brands or adopting foreign lifestyle trends.

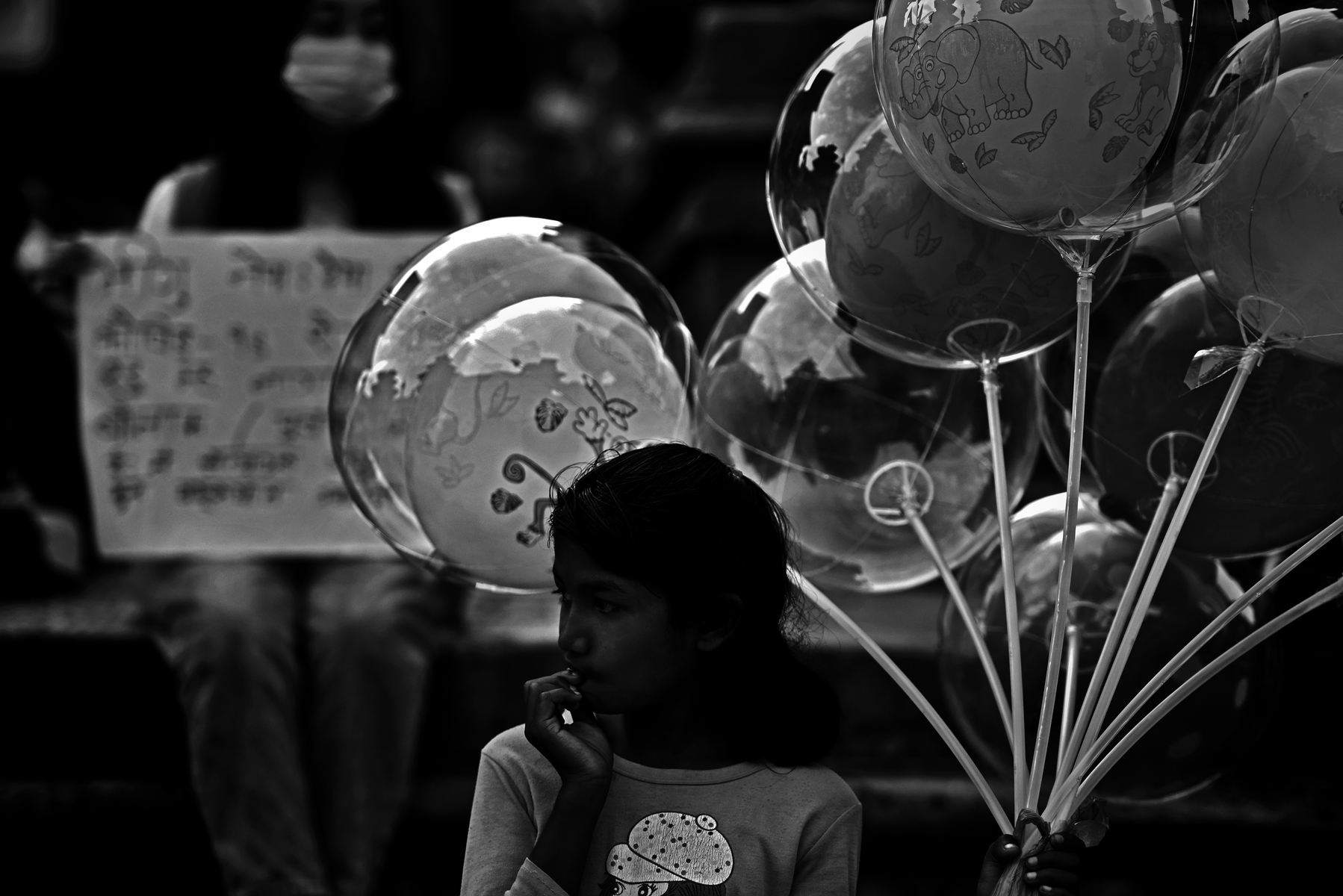

However, at the end of the day, the protest remained just that—a protest. Many young members of the Newar community from the Kathmandu Valley participated, but they were not at the forefront. Unfortunately, there seemed to be a disconnect between protesting for broad societal change and actively engaging with urgent, local issues that affect their own community—such as the Khokana land dispute, Smart City development, road expansion projects (Sadak Bistar), and the controversial Guthi Bill. These are matters deeply tied to the preservation of Newar heritage and identity.

In conclusion, if protests are to drive meaningful change, they must extend beyond Kathmandu Valley and reach places like Jumla, Rukum Rolpa, Taplejung, and the rural Tarai and hill regions. Without inclusive, nationwide engagement, protests risk becoming symbolic acts with limited real-world impact—a political mirage rather than a movement for transformation.